By James W. Conroy, Ph.D. May 2021

From 1908 to 1987, about 10,600 people lived at Pennhurst. We don’t know for sure how many people died there, but it was probably around half. Over the years, many people were discharged, ran away, or, toward the end, moved into small family-like community homes.

It was called the Eastern State Institution for the Feeble Minded and Epileptic when it opened in 1908, later the Pennhurst State School and Hospital, and finally just the Pennhurst Center.

It was designed and intended only for people with the disability now called developmental disabilities, or intellectual disabilities – and in the past we used terms like feeble-minded, idiot, imbecile, moron, and mentally retarded. Those terms are now out of date and offensive to our brothers and sisters who live with this kind of disability.

Its fundamental purpose was to get these people far away from society and never let them reproduce. The theory was that, eventually, they would be removed from the human gene pool.

By 1970, America had 293 places like Pennhurst, with nearly 200,000 Americans in them. Their conditions, in spite of the fervent efforts of caring workers, became horrible beyond description. It was the lack of funding, and the gross uncaring of society that wanted them "hidden away," that made it impossible for the workers to provide a decent humane abuse-free life.

(Pennhurst and places like it were never intended for our citizens with mental illness. Those citizens endured their own huge and abusive system called "state psychiatric hospitals." Their story is completely different from that of Pennhurst and developmental disabilities.)

So why is Pennhurst so important in the disability rights movement?

Because three huge social changes began here, with three great legal battles of right against wrong.

- A right to education (PARC versus Pennsylvania, 1972).

- A right to live in regular homes in everyday neighborhoods (Halderman versus Pennhurst, 1978).

- A right to treatment to improve their lives without abuse and neglect (Romeo versus Youngberg, 1982).

In 1978, after a long trial, a Federal Court (Halderman versus Pennhurst, 1978) decided that the people at Pennhurst were illegally segregated, abused, and harmed.

The judge ordered that every person get a chance to live in a regular home in a regular community with whatever supports and services they needed to thrive.

The idea that the people at Pennhurst could or should live, learn, have fun, and work in regular everyday neighborhoods was revolutionary in 1978. It was by no means clear that it would “work.”

There were 1,156 people at Pennhurst in 1978, and they had very serious differences from “normal” citizens. About 8 out of 10 had been found to have IQs below 35. (The average is 100 among all Americans. IQ is not talked about very much in modern disability work. But it was the main diagnostic tool back then.) About half used verbal communication very little or not at all. About half had not learned to be continent and were kept in diapers – mainly because there were not enough staff and not enough time. A third had epileptic seizures. More than a third had learned to attack others to protect themselves in the institution, which was then called “maladaptive behavior.” Actually it was very adaptive. It wasn’t until the 1990s that survivors who could speak revealed that almost all of them had been hurt, abused, and raped while living there. For those who could not speak, who were the most vulnerable of all, no one knows. The people at Pennhurst were not mad or violent or dangerous when they got to Pennhurst, usually as children. A few became that way after being at Pennhurst for a few years. But they too were children from loving families when they got to Pennhurst.

One by one, with careful planning, the people moved from Pennhurst to three-person “Community Living Arrangements,” now often called group homes. This process began under court order on March 17, 1978, and continued until closure on December 9, 1987. Nearly all of the people went to three person group homes that had staff on duty 24/7. They were everywhere, located in neighborhoods all across Southeastern Pennsylvania.

Q: Were the People Better Off After Leaving Pennhurst?

A: Yes, in practically every way we knew how to measure.

The now world-famous and classic Pennhurst Longitudinal Study was set up to follow the people from Pennhurst to their new community homes and find out how they fared after leaving Pennhurst. The study followed all 1,156 people who lived at Pennhurst in 1978. Every person was visited face to face every year, extensive quality of life and service data collected, and every family was sent a survey about their perceptions. We learned more about their quality of life over a long time than any other group of people with disabilities in history. The study had one question: “Are the people better off than they were at Pennhurst?”

- How many wound up homeless?

Zero.

- How many wound up in jail?

Zero.

- Did they live longer than they would have?

Yes, by at least 6 years.

- Were they healthier?

No, they were about the same, and got reasonable health care.

- Did they become more independent?

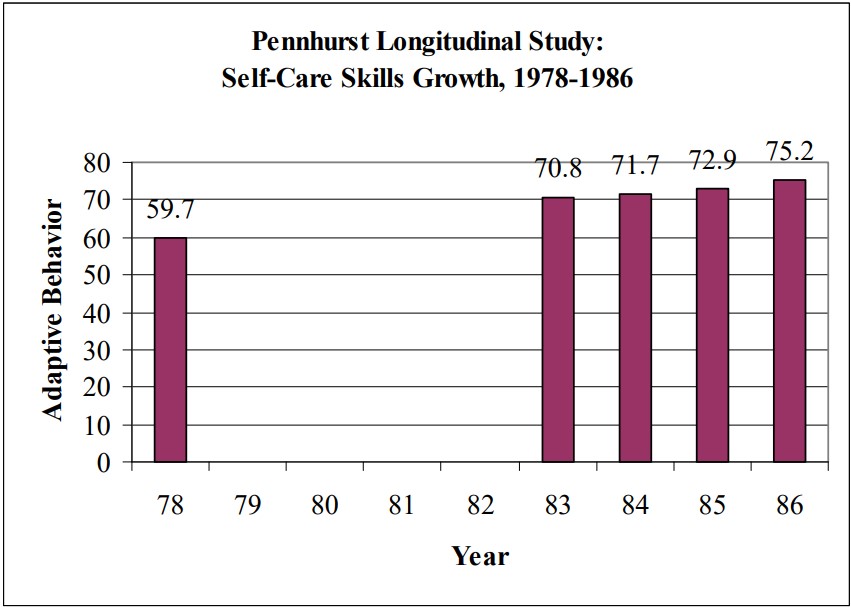

Yes, by at least 14% on a very accurate scale, shown below.

- Did their challenging behaviors decrease?

Yes, by at least 3%.

- Did they receive as much service to assist and learn?

Yes, much more, by about 19%.

- Were their homes better?

Yes, much higher quality on three scientific measures.

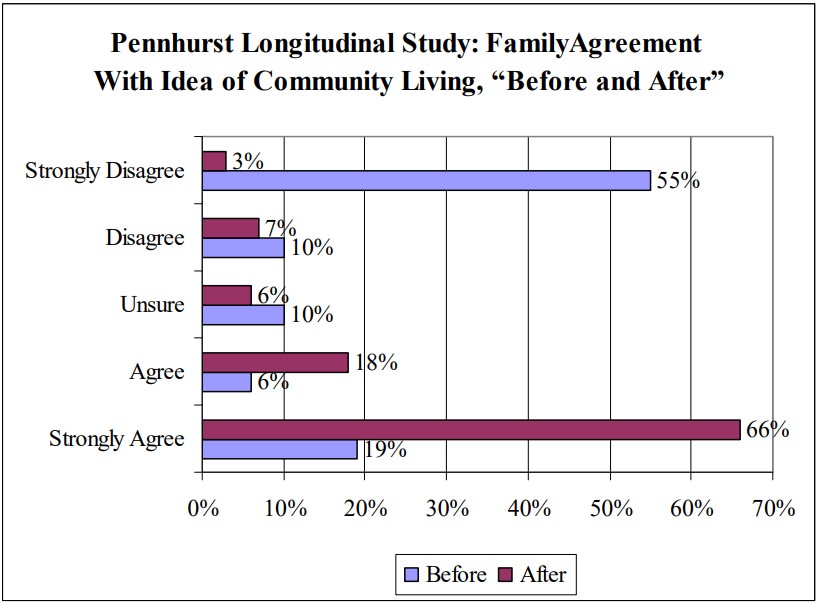

- Did families think they were better off?

Yes, overwhelmingly. Look at this graph.

- Did the people themselves say they were better off?

Yes, overwhelmingly, those who could speak said Yes. In 14 years of interviews, only 6 reliably said they wished they could go back.

- Did it cost more in the community?

No, the opposite, Pennhurst folks had far better outcomes and quality of life in the community with 15% less taxpayer dollars.

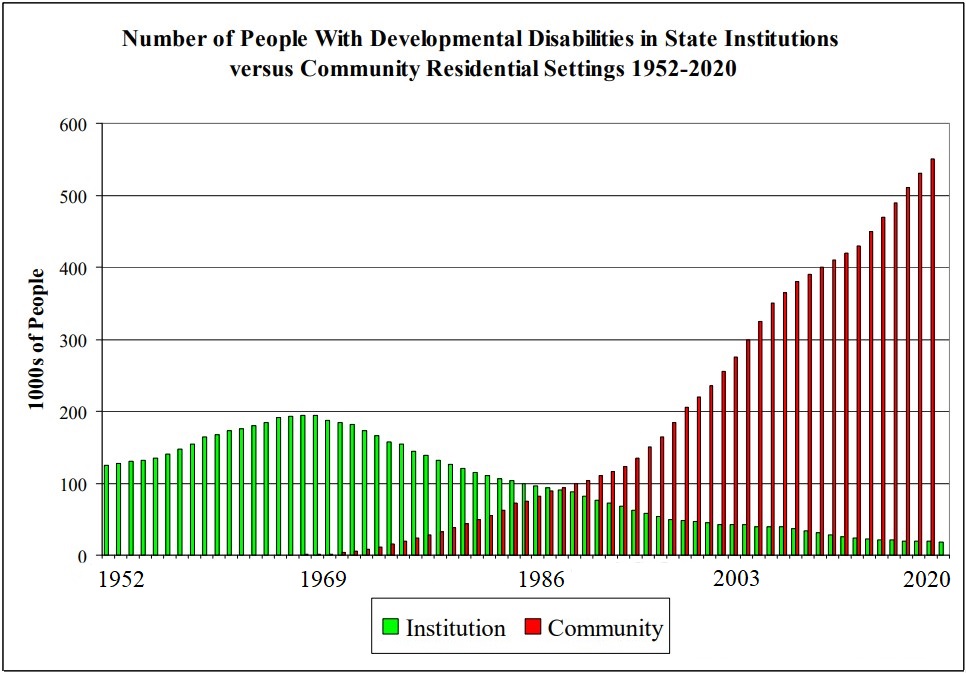

- Because of what we learned from Pennhurst, how many people moved from institutions to community homes – or avoided moving into institutions – in the past 50 years?

About 150,000 moved out of public institutions, and about a half million never went into them.

Summary

- Moving people from institution to community was one of the most successful social changes of the late 20th century.

- As of 2021, fewer than 15,000 people live in public institutions (down from the 1969 peak of 190,000), and 17 states have no public institutions at all.

- The Pennhurst experience contributed powerfully to a great civil rights movement that very few people know about.

- The terror and agony of the people who lived there was not in vain. It changed America and the entire world.