by Lou Chapman (1980)

Preface

The following account is the result of an invitation issued by Dr. James Hirst, Director of Psychological Services and Chief Advocate of Human Rights, on behalf of Pennhurst Center, to parents and friends of individuals residing at the institution to "live-in" on a ward. The purpose was to gain a better appreciation for the life-style of the residents.

Pennhurst Center, an institution housing about 1,000 people labeled mentally retarded, has been the subject of controversy over the years. In May, 1974, a group of residents filed suit against Pennhurst charging that they were forced to live in inhumane and dangerous conditions. Almost four years of legal proceedings resulted in Federal Judge Raymond Broderick' s Order that community programs be provided for all Pennhurst residents to replace care within the institution. The decision was immediately appealed by the County and Commonwealth. On December 13, 1979, the Third Circuit Court of Appeals, while not requiring Pennhurst's closing, did uphold the right of people to live in the least restrictive environment with continued emphasis on community placement. I volunteered to participate in the live-in. Although I spend a good bit or time "on grounds" as a member of the Pennhurst Human Rights Committee, I was concerned about my ability to understand what the people who live there really experience. Having been in administrative positions in the past (primarily in the ARC movement), I am acutely aware of how quickly one loses contact with those one is trying to represent. The "distance" (not necessarily physical distance, but rather the distance that derives from lack of understanding) separating the people making the decisions from those whose lives are affected by the decisions, very often is enormous. It is important, I feel, for all of us who are in the field of human services to be conscious of this "distance" and to make attempts, wherever possible, to increase our level of understanding. My live-in did help lessen the distance, and I began to have a much deeper appreciation for the people who live at Pennhurst.

The majority of my comments, I believe, reflect the institutional setting: whether it's a Pennhurst, whether it's a mental health facility, or whether it's a nursing home; wherever large numbers of people are gathered together who are devalued by society, wherever people are seen as a "group" rather than as unique individuals. I believe the system fosters the situations and attitudes that produce the kinds of feelings I had while I was there. This happens even with good staff who have good intentions, as have many of the staff at Pennhurst. It's awfully easy -- I realize this in myself -- to point to someone and say, "It's his fault," or "It's her fault," when at it's really all our faults. It's all of us collectively as part of society who have fostered "the system" and the attitudes. We may not have contributed directly to the isolation and devaluation of people with mental retardation, but we may have in some way isolated and devalued some other group of people. ("Polacks don't know anything." "I don't want my mother living with us -- she's too old, she'll cramp our life style." "Do you know that black people bought that house down the Street? There go our property values.")

My two day "live-in" experience at Pennhurst Center was in October of 1979.

Prior to going in, I thought, "Well, 48 hours isn't very long. I won't go in with any set of expectations, because I doubt if I'll get much out of it in only 48 hours." I was surprised to discover some of the feelings I did have in that very short period of time. Those feelings had a profound effect on me.

Observations

My home for 48 hours was Quaker Hall II, with fourteen women classified as severely and profoundly retarded. I tried to live there as a resident, not to monitor the situation, but to experience it in a feeling and sensory way. Obviously, I could not accomplish that completely since people knew I was on the Human Rights Committee. However, I did make an effort to integrate myself into the group of women who live there. I ate with them; I slept with them; and I did not leave the ward for 48 hours. It was obvious that certain efforts had been made anticipating my arrival on the ward, and I think that's human nature. Probably most of us would do the same in similar situations. When I first went on the ward, it struck me that ten of the women were wearing brand new white sneakers. They were glaring like flashlights. A staff person remarked that perhaps I ought to spend time on every ward so that everybody would get new sneakers.

The staffing ratio was increased during the time I was there. Although two people per shift is the normal complement, they made an effort to have at least three people per shift during my stay, pulling staff in from other wards in order to do that.

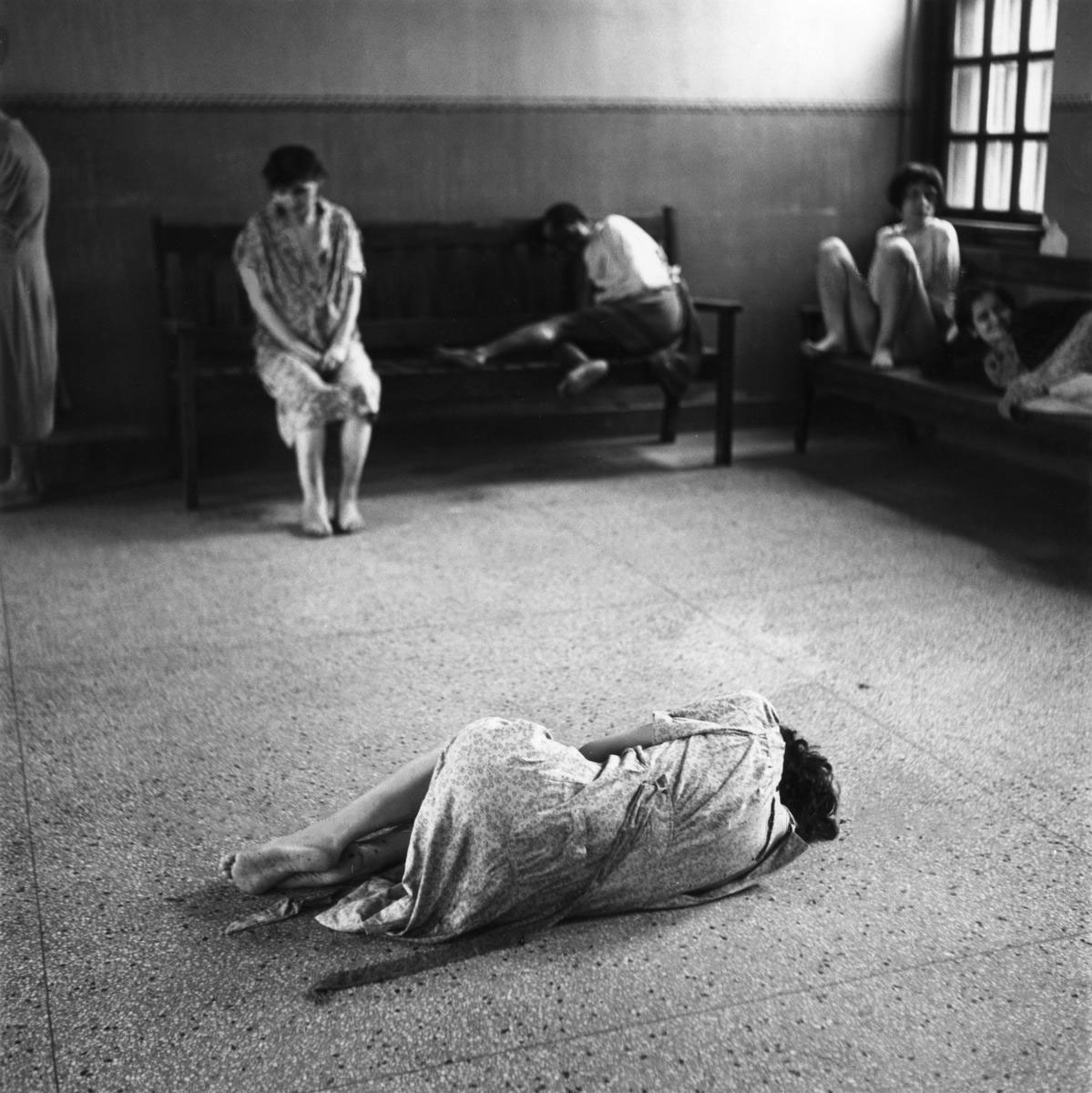

The women were dressed in their own clothes while I was there. I question whether this is done consistently. On the bulletin board was a memo that instructed staff to make sure the residents were dressed in their own clothes whenever there were to be parents or people from community programs on the ward. I found it interesting that special efforts are made at special times. One of the first things that impressed me was the behavior of these women. It reminded me of the behavior of individuals we call autistic, who have withdrawn from other people. They also had a good many kinds of institutional behaviors with which we are all familiar -- pacing, repetitive hand motions, rocking.

I think this behavior is an attempt to shut out the environment. The noise level on the ward was overpowering -- the television set was going 24 hours a day, literally, and at certain times the stereo was competing with the television. The noise level from that kind of stimulation and the noise level from the people themselves (the first night I was there, one woman spent most of the night screaming), is such that to survive in that kind of atmosphere you feel this need to withdraw -- to get away from the noise. Since one is unable to leave the ward, there is no place to withdraw except into oneself. The women all knew their own names, but it was extraordinary to me that they didn't know anybody else's name. Some of them have been living together for years but only one woman knew two or three of the other's names. Perhaps this, too, is part of the withdrawal process. The first time I went into the bathroom I was startled to look into the ‘mirrors." They're not glass mirrors; they're metal of some sort. You look in and your entire face is distorted. It was such a shock to me to look into this piece of metal and see myself! My face was all scrunched up. I thought, maybe that's really how some of these ladies perceive themselves. I was told that metal is used because they would break glass mirrors. Interestingly, there was a mirror, a real mirror, out in the hall. Nobody bothered it, so I doubt they would destroy mirrors in other places. The women all had the same haircut -- a bowl-cut with bangs. The clothing, while supposedly their own, was ill-fitting and in many cases inappropriate. Many of the women were in mini-skirts, and some shuffled around with their underpants falling down. The only objects available for our entertainment in the dayroom were children's stuffed animals, push toys, balls, coloring books, and some women's magazines. The people who live there range in age from 25 to 55. Not surprisingly, some of the staff treated the women like little children, referring to them as "my girls," "How's my little Gerry today?" or the "MR's".

These observations force me to ask: How would we feel about ourselves if we lived in that environment, where mirrors distort our faces, where as adults we are given toys, and where we all have the same haircut? I had some pretty strong feelings about myself, even over a short period of time -- and they were not positive.

I think we all are conscious of relationship continuity -- of building and maintaining relationships. Relationships are so important to all of us. I kept track of the number of staff people that those ladies and I had to interact with during the 48 hours I was there and found there were 27 different people who came in and out of our lives. The faces change constantly due to staff illness, vacations, and shortages. There are some who remain the same, but you see those people for very short periods of time.

Again, I have to ask how in the world would any of us develop relationships under that kind of situation where people drift in and out so quickly?

The staff was most sensitive to my privacy. They said, "Now, when you want to take a shower, you be sure and tell the staff." So the staff cleared out when I wanted to take a shower. I was asked if I wanted a privacy screen around my bed. (I didn't.) But I saw a very different attitude towards the people who live there. In fact, on the second shift, there were three men doing all the toileting and showering of the women. I had trouble just physically being there during this process seeing these men with their hands all over the women, during the showering and toweling. To me, it was terribly dehumanizing.

(I had a very interesting experience after I had related these observations to the Pennhurst Board of Trustees. The charge aide for that ward came up to me and said, "Do you know I never thought about it until you asked how we would feel being showered and toileted by a group of men we really didn't know. I wouldn't like it a bit, but I never had thought about it before. Thank you for saying it." Again, I believe the system fosters these attitudes. New staff come into the system where this is accepted behavior. No one questions it. Obviously, it's sanctioned by the administration. You tend to think, "Well, I guess it's okay. They're only people with mental retardation, so it's all right in this situation.")

What do these attitudes say about the dignity of the people who live there? Was I perceived as being more human than these women are? How would we feel about ourselves if those with whom we interact treated us that way?

Efforts clearly have been made to increase programming. However, I discovered that there seems to be a policy to conduct programming with groups of people, not on an individual basis. I was appalled at the way the group programming was done. It was totally and completely inadequate. There was one staff person trying to work with six women, and with the turmoil and the stimulation from the whole environment, there was no way effective programming could be accomplished, as far as I could see. At one point, the aide said to one person in the group, "Put the square in the hole." The resident then threw the block at the person across the table; meanwhile, her neighbor grabbed the board, while the women across the table was screaming. It was chaotic. The level of expertise of the staff doing the programming was disturbing also. Obviously, they hadn't received the kind of training they should have to deliver the programming the women need. In addition, one must question how meaningful the programming is in relation to the actual situation. Learning to put a square block in a square hole as an end unto itself bears little relationship to the day-to-day existence of the women who live on that ward. The psychologist for the ward has, on his own, said, "I am going to work with some of these women on an individual basis irrespective of the policy." He's making some strides. For example, he's been able to increase one woman's attention span from two minutes to three minutes. It's obvious to me that while these ladies are labeled severely and profoundly retarded, they've got a lot of potential if the environment were different, if they were given individual one-on-one programming, and if the staff were properly trained. I know they could progress beyond where they are right now. As things stand today, they do not have much chance of doing that. There are enormous amounts of time when nothing is done. The high point of the day is when someone smears herself with feces; she then gets a one-on-one shower with talcum powder added for good measure and returns to doing nothing. (One lady has forced "the system" to respond to her. She smears herself up to three and four times a day – she's a master at getting individual attention.) While some of these women have not given up inventing ways for attention, many others show complete resignation. In the course of the day and evening, where these huge gaps of time existed and nothing happened, we all just sat around in the dayroom staring at each other -- hardly stimulating. The feeling I had was of absolute lethargy. I could see this feeling transmitted to the staff, as well. The lack of stimulation was so great that it became an effort to get off the chair and move.

Again, I must ask, how would we learn and develop as individuals under these conditions?

During this time I had no contact with anybody outside of Pennhurst. I had no calls. I had no visitors. In spite of the fact that I knew I was leaving Wednesday afternoon, I felt totally and completely isolated and abandoned. I knew my friends were out there, and I knew I was leaving; yet in this short period of time I thought nobody cared about me. It's difficult to tell the time of day. It's difficult to tell the weather. It's difficult to focus beyond the heavy mesh window screens. You are so totally isolated from the outside world that you feel there is no outside world -- that the sum total of existence is contained in this room.

Wednesday morning was a dark dismal day -- generally depressing. In the middle of the morning with no programming in progress, I found myself in front of the window . . . actually pacing. (Unlike General MacArthur I do not pace ordinarily.) I had to suddenly stop myself when I realized what I was doing. It became so apparent to me why so many people have institutional behaviors. My God -- any of us would have then if we spent very much time there. I'm absolutely convinced of it.

Over the years, we have spent hundreds of thousands of dollars developing evaluation tools, and I certainly support appropriate evaluation tools. However, I think that all of us have a very easy way of evaluating any kind of living situation for anybody. That is simply to ask, "Would I want to live there?" If the answer is no, then why in the world do we in any way support another human being living there?

John Vanier, founder of the L'Arche movement, whom I had the great fortune of meeting a year and a half ago in Vienna, talks very deeply and profoundly about the sensitivity of handicapped people:

A mentally retarded person can lead a deeply sensitive life, a life of the heart, which tends to draw him into close relationships with other persons and by which he can be protected, guided, and encouraged along the path of human and spiritual progress. The mentally retarded person . . . is essentially a person of heart and of deep sensitivity1.

He also talks about the "wounds" that handicapped people have had inflicted upon them in many subtle ways by all of us -- being seen as a set of "problems"; being called "kids," "my boys and girls," or by one's last name only; being talked about as though you weren't there; being rejected. People who live in institutions receive wounds, daily.

1My Brother, My Sister by Sue Mosteller